Major new global study identifies a safer treatment of acute stroke

The safety of a controversial clot busting drug has been investigated by researchers at The George Institute for Global Health, with results showing a modified dosage can reduce serious bleeding in the brain and improve survival rates.

It is hoped the findings from the trial of more than 3000 patients in 100 hospitals worldwide could change the way the most common form of stroke is treated globally.

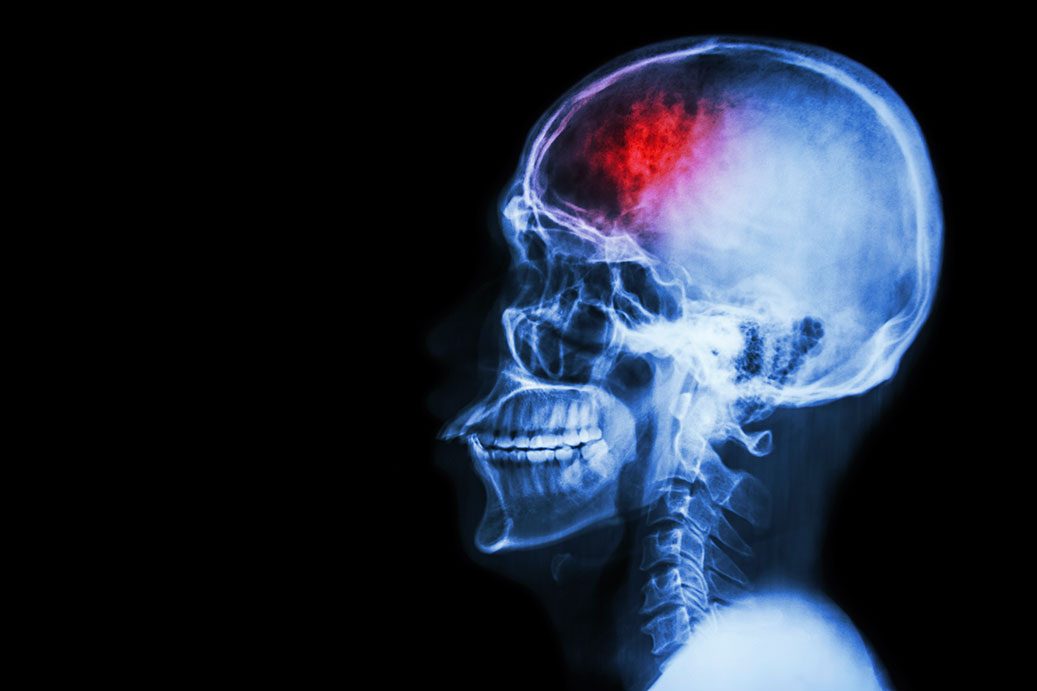

Intravenous rtPA (or alteplase) is given to people suffering acute ischaemic stroke and works by breaking up clots blocking the flow of blood to the brain. However, it can cause serious bleeding in the brain in around five per cent of cases, with many of these proving fatal.

Professor Craig Anderson, lead author of the study published in The New England Journal of Medicine, said: “At the moment you could have a stroke but end up dying from a bleed in the brain. It’s largely unpredictable as to who will respond and who is at risk with rtPA.

“What we have shown is that if we reduce the dose level, we maintain most of the clot busting benefits of the higher dose but with significantly less major bleeds and improved survival rates. On a global scale, this approach could save the lives of many tens of thousands of people.”

Key findings

- Compared to standard dose (0.9mg/kg body weight), the lower dose (0.6mg/kg) of rtPA reduced rates of serious bleeding in the brain, known as intracerebral haemorrhage (ICH), by two thirds.

- After 90 days, 8.5 per cent of patients had died after receiving low dose rtPA, compared to 10.3 per cent who received the standard dose.

- The survival benefit was offset by a slight rise in the amount of people suffering residual disability. For every 1000 patients treated, low dose rtPA, compared to the standard dose, 41 more people had physical disabilities, such as needing help dressing or walking, but 19 fewer people died.

These differing effects meant that the trial was unable to show conclusively that the low dose was as effective as standard dose rtPA in terms of survivors being free of any disability.

rtPA is used to dissolve clots that block a blood vessel in a patient’s brain within the first few hours after the onset of stroke symptoms. Yet, because many people with stroke arrive at hospital after this crucial time window, only around five per cent of eligible people currently receive this therapy in most countries.

Professor Anderson, of The George Institute for Global Health, said he hoped the lower dose would become the standard in situations where a doctor considers the risk of ICH to be high in a particular patient.

Professor Anderson, who presented the findings at the European Stroke Organisation Conference in Barcelona, added: “There is a trade off with the lower dose in regards to recovery of functioning, but being alive is surely preferable to most patients than suffering an early death.”

National Coordinator of the study in the United Kingdom, Professor Tom Robinson of the University of Leicester, emphasises that: “The results of this trial provide important information when discussing clot-busting treatment with patients and their families. Most patients who have a major stroke want to know they will survive but without being seriously dependent on their family. We have shown this to be the case with the lower dose of the drug.”

Concerns over the risks of ICH associated with rtPA has prompted independent reviews of the research evidence in Australia and the United Kingdom. In Australia, the College of Emergency Medicine has refused to endorse use of rtPA despite all national stroke guidelines recommending the treatment.

The number of ischaemic strokes each year in particular countries is estimated at 40,000 in Australia, 120,000 in the UK, 640,000 in the USA, 1.2 million in India, and 2 million in China.