Making it compulsory to reduce salt in foods could save thousands of lives

Mandating stringent targets for sodium levels in Australian packaged foods in line with World Health Organization (WHO) recommendations could prevent around 40,000 cardiovascular events (including heart attacks and strokes) and up to 3,000 deaths over a ten-year period, according to new research published today in The Lancet Public Health.1 Around 32,000 new cases of kidney disease could also be avoided and some AUD3.25 billion in healthcare costs for these diseases saved over the population’s life span.

Led by researchers at The George Institute for Global Health in collaboration with Griffith University, UNSW Sydney and Johns Hopkins University*, the study is the first to project the long-term impacts of setting mandatory sodium reduction targets for processed foods, comparing the Australian Government’s current voluntary benchmarks with the higher targets recommended by the WHO.2

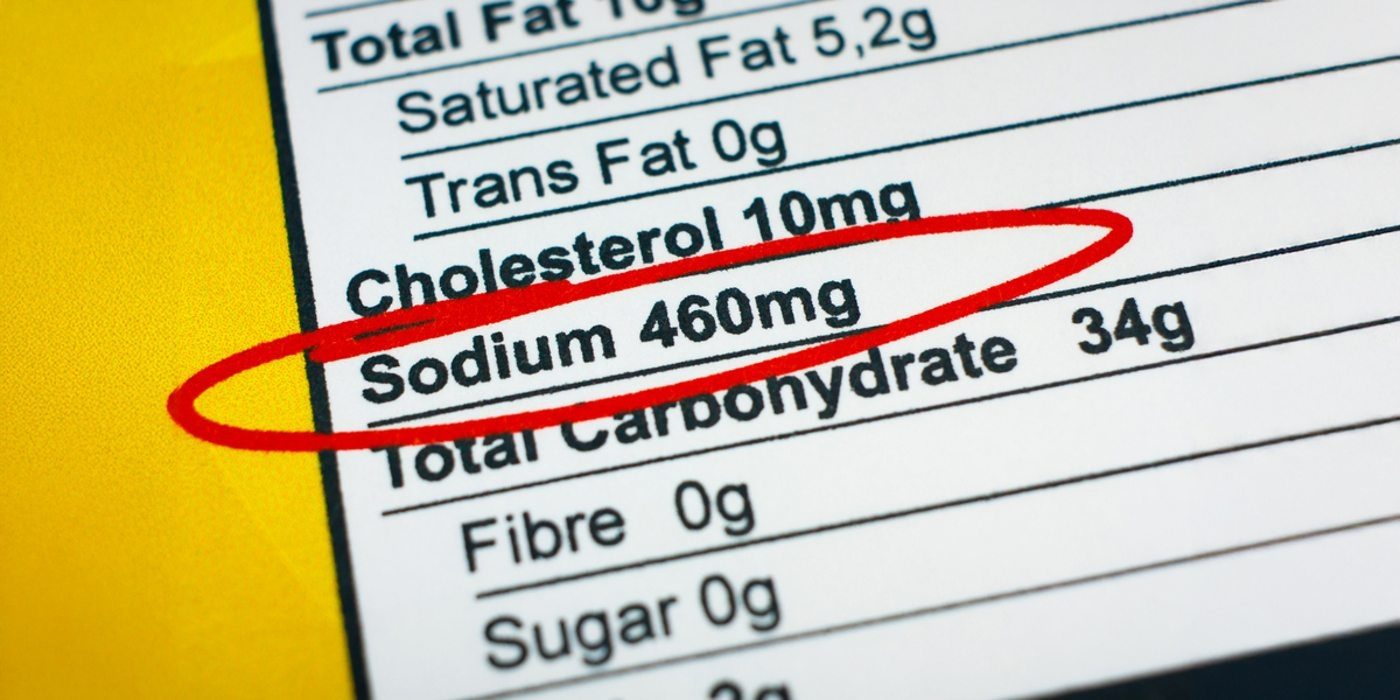

Excessive sodium intake is a major killer globally, contributing to cardiovascular disease (CVD) and chronic kidney disease (CKD).2,3,4 In Australia, average daily consumption is almost double what is recommended by the WHO, with the majority coming from salt hidden in foods like processed meats, bread and bakery products, cereal and grain products, and dairy products.5,6

Professor Jason Wu, Head of Nutrition Science at The George Institute and Professor at UNSW Medicine and Health’s School of Population Health and an author on the study, said the analysis shows that setting sodium reduction levels higher than the current Australian targets, and making them mandatory, could bring significant health benefits and reduce the burden of CVD and CKD on the healthcare system.

“Our study projected enormous reductions in both cases and deaths from heart attacks, strokes and other heart conditions, as well as from kidney disease, within just a decade if the WHO reduction targets were mandated. Beyond ten years, we also showed that this reduction in disease burden could generate billions of dollars in savings from healthcare costs related to these diseases,” he said.

The WHO recommends reformulating food products to reduce sodium levels as part of its goal to decrease sodium consumption by 30% globally by 2025.7 This is also a component of the Australian Federal Government’s Healthy Food Partnership (HFP), launched in 2015, which asks the food industry to reduce sodium levels across 27 food categories, among other measures to support healthy eating.8

“Australia’s sodium reformulation targets not only remain voluntary, but are also less rigorous than the WHO sodium benchmarks. We see industry consistently failing to meet voluntary targets and this weak regulatory system means Australia is missing an opportunity to protect its people from harmful effects of eating too much sodium,”9 Prof Wu added.

“Other countries such as Brazil, Mexico, Spain and Malaysia have adopted mandatory sodium limits, so it can be done. We have now shown that if Australia adopted these more effective benchmarks and made them compulsory, it could help relieve the strain on our healthcare system over the next few decades.”

Griffith University’s Dr Leopold Aminde from the School of Medicine and Dentistry said the research exemplifies the reasons why Australia must now move away from a voluntary approach to mandating sodium thresholds for packaged foods.

“Curtailing excessive sodium consumption has the ability to prevent thousands of deaths and cases of cardiovascular disease and chronic kidney disease, coupled with the added economic cost-saving benefits for Australia’s health system,” Dr Aminde said. “Our analysis shows these benefits could be three-to-four times greater when stringent sodium thresholds, such as those proposed by the WHO, are mandated compared to the existing voluntary targets.”

Dr. Luz Maria De Regil, Head of the Multisectoral Actions in Food Systems unit, Department of Nutrition and Food Safety at the WHO said, “With only voluntary measures in place to reduce sodium in the food supply, Australia may not offer to all its population adequate protection from heart attack, stroke, and other health problems. The WHO is calling on all countries to implement our ‘best buy’ interventions for sodium reduction, and on governments to mandate that manufacturers implement the WHO benchmarks for sodium content in food.”

The variation in benefits from mandating WHO or Australian targets is shown below:

MANDATING AUSTRALIAN TARGETS 100mg per day reduction in sodium consumption | MANDATING WHO TARGETS 400mg per day reduction in sodium consumption |

|---|---|

| 13,000 fewer new cases of CVD over ten years | 44,000 fewer new cases of CVD over ten years |

| 18,000 CVD deaths from CVD averted over lifetime (75 years) | 64,000 deaths from CVD averted over lifetime (75 years) |

| 9,000 fewer new cases of CKD over ten years | 32,000 fewer new cases of CKD over ten years |

| AUD940 million saved from healthcare costs related to heart attacks, strokes, and kidney disease over the population’s lifetime | AUD3.25 billion saved from healthcare costs related to heart attacks, strokes, and kidney disease over the population’s lifetime |

* ‘The estimated health impact, cost, and cost-effectiveness of mandating sodium benchmarks in Australia’s packaged foods modelling study’ is part of a collaborative program of research led by The George Institute for Global Health and UNSW School of Population Health, supported by School of Medicine & Dentistry, Griffith University; and Center for Human Nutrition, Department of International Health, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

References:

1. Marklund M, Trieu K, Aminde LN, Cobiac L, Coyle DH, Huang L, et al. Estimated health impact, cost, and cost-effectiveness of mandating sodium benchmarks in Australia’s packaged foods: a modelling study. The Lancet Public Health. Vol 9, November 2024

2. World Health Organisation. Salt Reduction. WHO. 2020. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/salt-reduction

3. Heart Foundation. Key statistics: Risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Heartfoundation.org.au. 2017. Available from: https://www.heartfoundation.org.au/your-heart/evidence-and-statistics/key-statistics-risk-factors-for-heart-disease

4. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Heart, stroke and vascular disease—Australian facts. AIHW. 2023. Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/heart-stroke-vascular-diseases/hsvd-facts/contents/about

6. Saiuj Bhat, Matti Marklund, Megan E Henry, Lawrence J Appel, Kevin D Croft, Bruce Neal, Jason H Y Wu. A Systematic Review of the Sources of Dietary Salt Around the World. Advances in Nutrition. Volume 11, Issue 3, May 2020, Pages 677-686

7. World Health Organisation. Massive efforts needed to reduce salt intake and protect lives WHO. 2023. Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/09-03-2023-massive-efforts-needed-to-reduce-salt-intake-and-protect-lives

8. Healthy Food Partnership. Healthy Food Partnership Reformulation Program: Evidence Informing the Approach, Draft Targets and Modelling Outcomes. 2020. Available from: https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2021/04/partnership-reformulation-program-rationale-paper-food-reformulation-program-rationale-paper.pdf