Are we doing enough for the mental well-being of Community Health Workers during COVID-19?

CHWs engaged in contact tracing, transport, screening, and follow-up of patients with COVID-19 are at risk of developing psychological distress and mental health symptoms. A mental health response is therefore needed to support CHWs during and after the coronavirus response reaches crisis levels in local regions. This response should recognize the unique needs and challenges of male and female providers. Around the world, some health systems are developing and implementing strategies to offer such support to formal frontline care workers. However, evidence-based guidelines to inform mental health care for CHWs, especially during public health emergencies, remain scarce.

How do organisations support the mental health and well-being of community health workers?

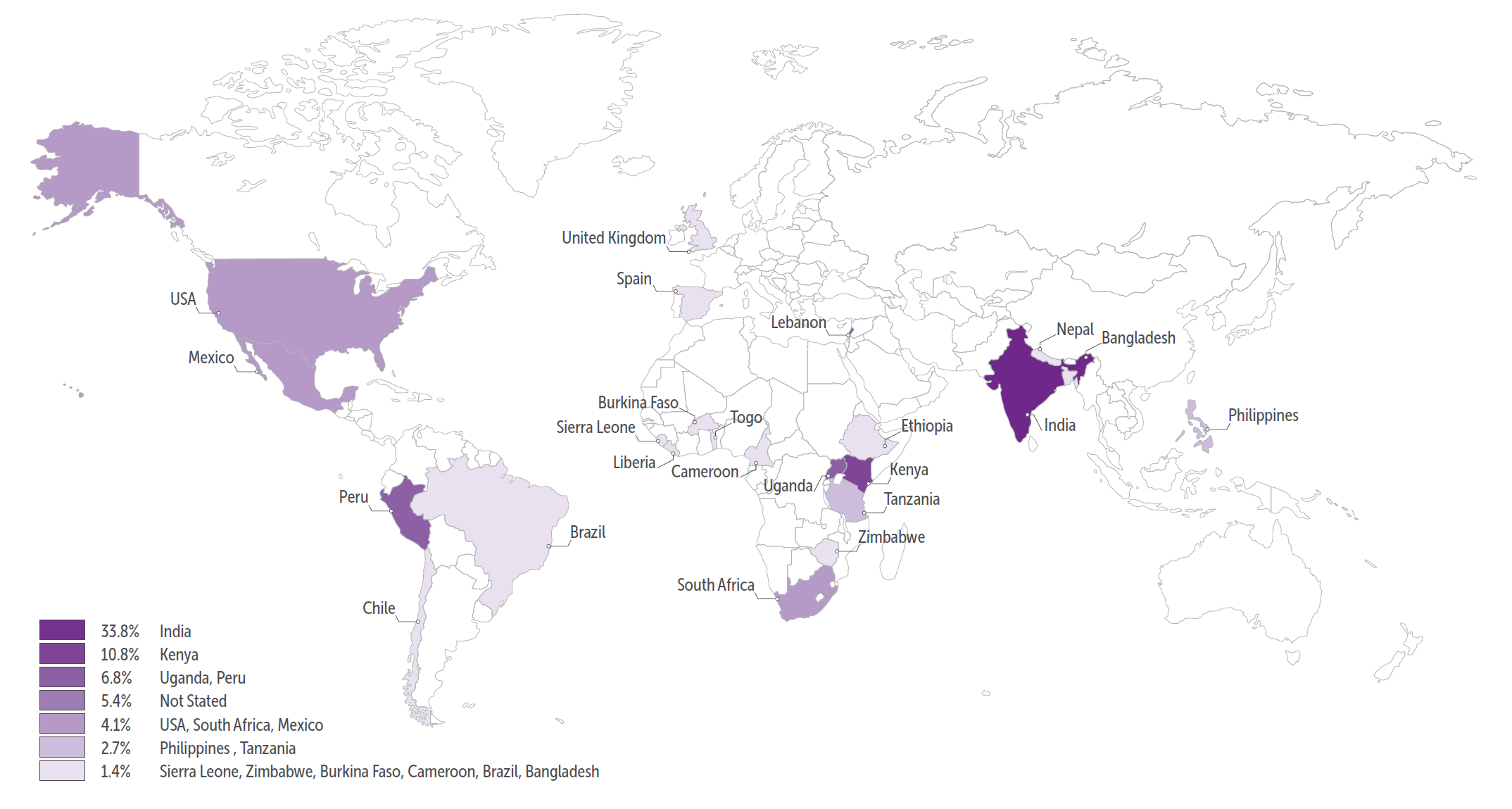

We aimed to explore the availability of resources that support the mental wellbeing of CHWs in LMICs during the COVID-19 pandemic in collaboration with the Thematic Working Group on Community Health Workers of Health Systems Global. We crowdsourced resources via a Google survey from 25th May to 8th June 2020. Overall, 103 participants responded from 23 countries (Figure 1). Sixty-one responses were included in the final analysis as the rest were either duplicates, from representatives at the same organisation, or empty responses. Both The George Institute and the Thematic Working Group thank all those who participated in the survey.

Fig 1: Countries where the responses came from

Representatives of 57.4% of the organisations reported noticing mental health symptoms among CHWs. Of those reporting mental health systems, 76.5% noted core mental health symptoms such as anxiety, depression, and increased stress, the second leading group of symptoms (70.5%) were undifferentiated (e.g. somatisation, fatigue, insomnia etc), followed by complaints of high workload and burnout (14.8%).

Approximately half (50.8%) of all organisations reported that they offered some mental health interventions such as training for mental health support (online or face- to-face) (22.8%), psychosocial support (WhatsApp group, peer support) (61.3%), pharmacotherapy (9.7%), increased supervision (6.5%), and rehabilitation for other mental health disorders (6.5%). Most of the mental health services were delivered in India (45.2%). We did not seek to explore the implementation and uptake of the reported interventions.

Of the organisations offering support, six were international NGOs/Foundations; two were Universities/Research centres; 18 were local hospitals/clinics/community-based organisations, three were Ministry (all national-level), and one was unknown type. These data suggest that most mental health support is provided by local organisations and institutions.

Conclusion: CHWs working during COVID-19 must be given the space to talk about their feelings and take care of their own mental health. However, they are facing challenges while performing their tasks therefore need to be supported through evidence-based interventions which are low-cost, accessible, gender-sensitive and easily implemented.

Key messages

- Fifty-seven percent of organisations involved in the survey noticed mental health signs and symptoms such as anxiety, depression and stress among CHWs during the COVID-19 pandemic

- Approximately fifty percent of organisations provided some mental health support to CHWs such as online training, peer support via WhatsApp

- These interventions have not been evaluated so far

- More effort is needed to support the mental health and wellbeing of CHWs in LMICs during and after the pandemic

Next steps: We plan to have a workshop to identify strategies for:

- disseminating gender-sensitive resources to CHWs, especially those working in LMICs, that can help them manage symptoms of anxiety, depression, and other symptoms of mental distress;

- encouraging uptake of such resources, despite stigma around mental illness and competing demands on the CHWs’ time;

- developing a plan for evaluating the acceptability and effectiveness of these resources during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Reference

Ajisegiri WS, Odusanya OO, Joshi R. COVID-19 Outbreak Situation in Nigeria and the Need for Effective Engagement of Community Health Workers for Epidemic Response. Global Biosecurity 2020; 1: http://doi.org/10.31646/gbio.69.

Ballard M, Bancroft E, Nesbit J, et al. Prioritising the role of community health workers in the COVID-19 response. BMJ Global Health 2020; 5(6): e002550.

Jha N. India’s first line of defense against the coronavirus is an army of 900,000 women without masks or hand sanitizer. Available: https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/nishitajha/india-coronavirus-cases-ashas, 2020.

Rao B. Promised, Mostly Never Paid: Rs 1,000 Covid Wage. https://www.article-14.com/post/promised-mostly-never-paid-rs-1-000-covid-wage-to-million-health-workers, 2020.

Rao B, Tewari S. Distress Among Health Workers In Covid-19 Fight. https://www.article-14.com/post/anger-distress-among-india-s-frontline-workers-in-fight-against-covid-19, 2020.

Adhanom Ghebreyesus T. Addressing mental health needs: an integral part of COVID-19 response. World psychiatry : official journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA) 2020; 19(2): 129-30.

United Nations. Policy Brief: COVID 19 and the Need for Action on Mental Health, 2020.

Vigo D, Patten S, Pajer K, et al. Mental Health of Communities during the COVID-19 Pandemic. . Can J Psychiatry 2020: 706743720926676.

Boyce MR, Katz R. Community Health Workers and Pandemic Preparedness: Current and Prospective Roles. Frontiers in Public Health 2019; 7(62).

De Sousa A, Mohandas E, Javed A. Psychological interventions during COVID-19: Challenges for low and middle income countries. Asian J Psychiatr 2020; 51: 102128.