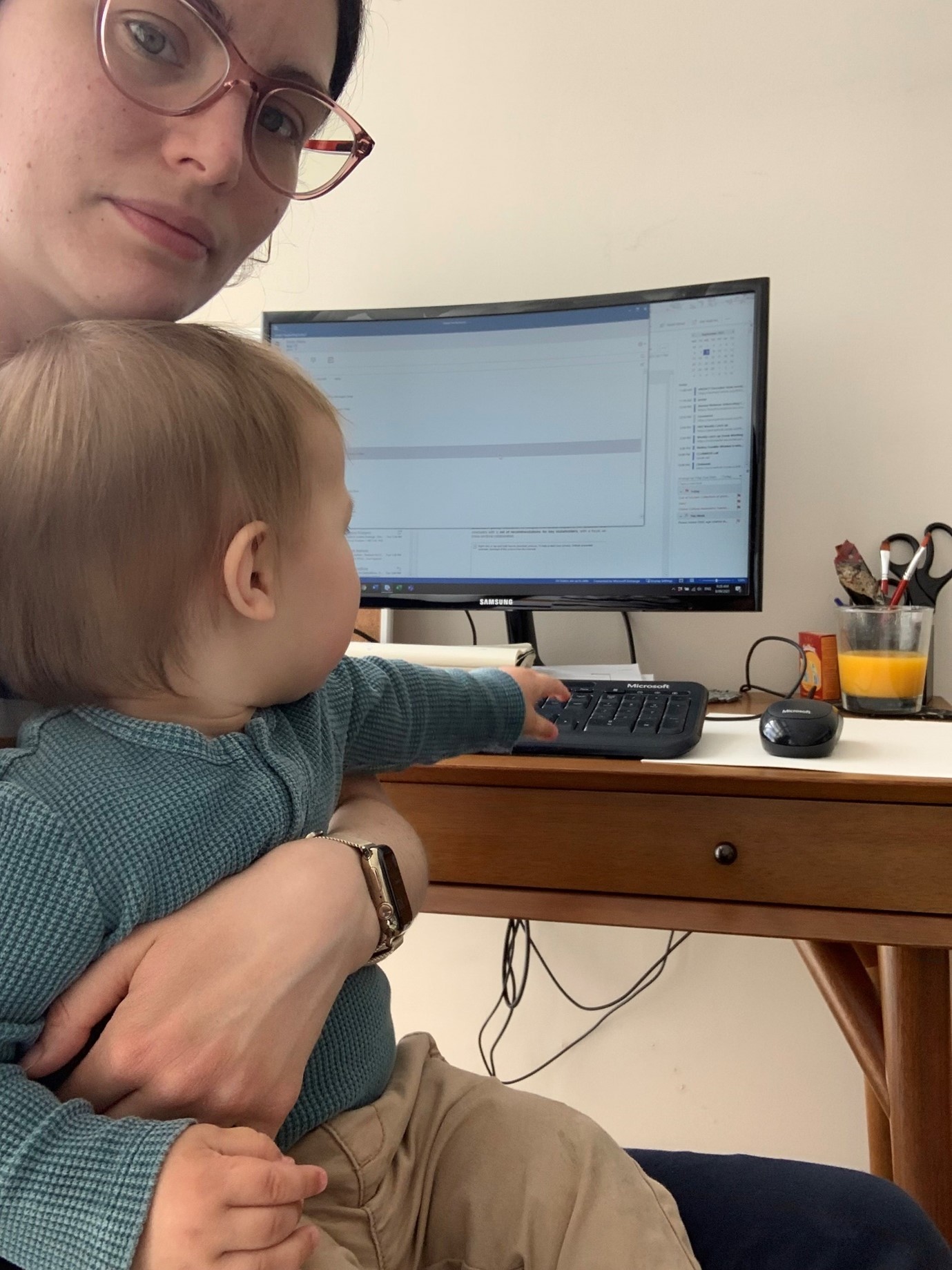

Blog by Dr. Emily Atkins: Five fundamentals of returning to research after parental leave

This reflection started as a response to discussions with Franklin Women and the High Blood Pressure Research Council Australia in early December - I was keeping notes on my phone about how the way you work changes when you become a new parent. I was having trouble finding the time and energy to write it up… then in late February my toddler wasn’t sleeping well, and I decided to make use of the moments he slept in the early hours of the morning to write as a thread for Twitter. It seemed to resonate with a lot of parents, reminding them of the challenges they endured during their return to work. Those without children commented that having these things articulated helped them to understand these challenges. Here, I’ve followed the structure of the original thread but expanded a couple of points:

My toddler is sleeping in 20-minute intervals tonight, so I’m going to do a thread about returning to work from maternity leave. There are five things I want to cover: 1. Pumping 2. Day-care and illness 3. Sleep and memory 4. Time 5. Demands. This is based on my experience as a medical research institute-based academic in Australia. Many parents experience different hurdles in other settings.

Pumping at work

I returned to part time work when my son was seven months old - he’d started solids but still mostly breastfed, so I needed to pump twice a day. My work has a lovely little room with a comfy chair for this, thanks to another mum advocating for this space to be available. This takes about 15 minutes a side, plus 15 minutes to prepare and clean up, so total is 45 minutes each session, 90 minutes each workday. To reduce time spent pumping (and shoulder pain from holding pump) I bought a hands-free double pump - this saved me 15 minutes. As he got older, I only needed to pump once a day, and now no longer pump.

When I returned to work, I wanted to make up for lost time (maternity leave) on my projects and getting my grant applications submitted. I was worried about the time I ‘lost’ when I was pumping. I learnt to schedule my day around pumping and dropped meetings to get more focus time. This was hard.

Day-care and illness

Day-care takes interruptions to the next level - an infant in day-care catches an infection a month on average. And they share it with their family. In the pandemic, and especially during lockdown, every cough and runny nose meant a nasal swab and isolation. And time off work caring for sick child, then sick self. My husband and I share sick days 50/50, sometimes half days each, sometimes “I’ll do today, and you do tomorrow.” The weeks when he was sick, I was just scraping through, getting the urgent things done but not progressing anything else. It gets better as they get older, but it’s another big loss of ‘productive work time’ during the first year back from parental leave, and it’s not something you can plan. You start saying no to the extra things you used to do, because you need to get the important stuff done.

Sleep and memory

Another surprise was how badly interrupted sleep affects my memory. Often, I was up three times a night feeding and resettling. It’s now years since I’ve had a full night of sleep. I forget whole conversations - it’s embarrassing, and something I worry about. I ask people to email me a prompt of what they are asking me to do. Then every morning I have an inbox of ‘to do’ items for other people. And that manuscript I was writing gets forgotten, and when I remember it, I’m no longer sure if it’s any good. Bad sleep means a sad, anxious brain for me. I’ve been fortunate to have access to a psychologist (initially through the Employee Assistance Program) during the transition to working motherhood. After a year of hoping we’d grow out of night feeds and multiple wakes, I’ve also had a sleep consultant help to establish a better bedtime routine for my family.

Time

I used to spend as long as I needed to get a task done, occasionally staying late in the office when I got into ‘flow’ on a particular project, or when I had a hard deadline. Now I absolutely must leave work on time now to get to day-care for pick up. I can’t stay late to finish this last analysis. It doesn’t matter if I just hit ‘flow’ on writing the manuscript. Day-care charges late fees in 15-minute increments. I skip the impromptu social thing too, even though I’d love to catch up and find out what my colleagues are up to. With a little warning I can sort it out with my spouse to do pick-up, dinner, bath, and bedtime alone – but it takes a bit of preparation.

Demands

So, when you’re asking a new parent to do something, give as much lead time as you can to return a draft or add to a grant application. Schedule short regular meetings if you need to meet. Email if you don’t (please include a clear action and due date). Take the pressure off expectations to be highly productive when first returning and be explicitly clear you don’t expect anything to be done during parental leave! And please think about this when you read the career interruption as you peer review grants. The period out of office might only be months but it is often the only indicator to show the candidate had a major shift in the way they can work. And their productivity and service contributions will drop in this time. And the pipeline of projects will slow. And this is okay and why we include ‘Relative to Opportunity’ in grants – but we need reviewers to understand and truly consider this.

I’m privileged to have the resources available to support my parental leave and return to work. Space for pumping, childcare, and flexible work options are all helpful. Support these in your institutions whenever you can.